A new geopolitical order is in the making and no one can be entirely sure where it will end, although several patterns are emerging. Inflation is increasing; deficit spending is in expansion and the risk of a very bad outcome for the world and for markets is on the rise. At the centre of events is Putin, a man who is afraid of close contact even with his political allies, but who is happy ordering the bombing of cities full of civilians. Since the conflict has been chosen and preannounced by Putin, his preferences and character will also determine the outcome, and he seems to be looking for a large, painful conflict, in order to show the world the importance of Putin’s Russia.

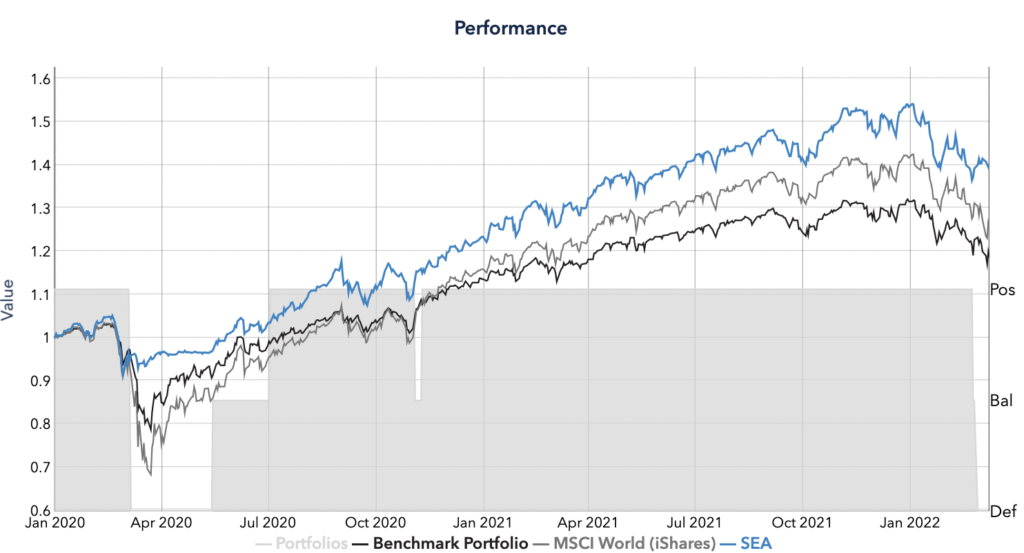

In the context of our investment process, the war and the resulting equity market declines added to an already negative momentum in our algorithms which, by late February, were signalling an increased probability of a more forceful market correction in which fear feeds on fear, credit spreads widen, equities decline, and markets correct further. We have therefore been reducing risk, moving from “Positive”, through “Balanced”, to “Defensive” allocations across all strategies, which all now hold portfolios of high-grade bonds. The rationale behind these moves, as always, is a desire to protect invested capital in times of an unfavourable risk-return trade-off and to prepare to capture market upside when the risk-return trade-off is more advantageous.

Figure 1. We moved to a “Defensive” positioning in late February to limit potential drawdowns

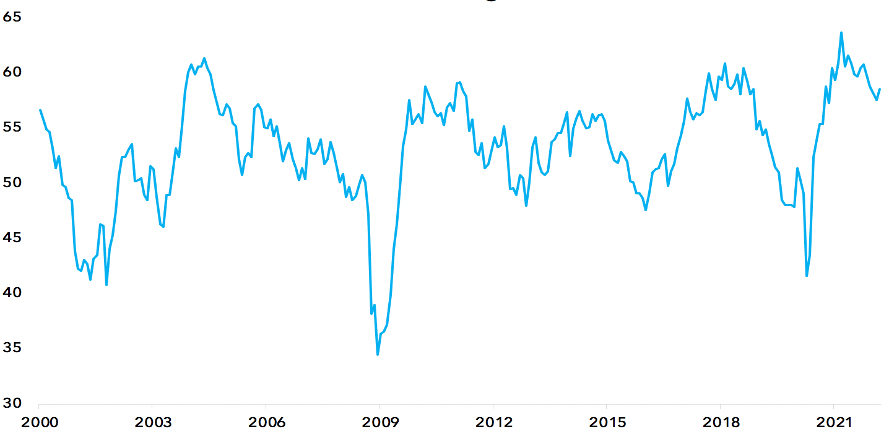

In an environment in which the Russian invasion is evolving in a way that no-one seems to have fully expected, and in which there is an ongoing development in sanctions, in the policies of individual countries and in the broader western response, uncertainty and pressure on the markets are developing across a broad set of areas. This is seen most intensely in commodity markets, where prices have moved higher and thereby add to fears of a prolonged inflationary pressure. For long term investments in fixed income instruments, such a development is obviously a potential threat. However, in the short run, the more fundamental forces of risk aversion often dominate, and medium duration bonds are likely to continue to deliver decent protection. Across our portfolios we are therefore holding short and medium duration US and Euro zone government bonds as the largest allocations. In some portfolios we also hold smaller allocations to equities and/or high yield bonds. When we do so, it always creates a well-diversified “Defensive” portfolio, with for example 20-25% US equities in a strategy where we can hold up to 100% equities. As reflected in the recent labour market statistics and US manufacturing sector confidence (see Figure 2), a global recession is still not the most likely outcome. The business cycle component of our algorithms is thus still positive and, barring further shocks to markets, we could be moving back into larger equity and high yield positions soon. For now, we are positioned as follows:

- We have reduced our equity allocation from 100% to between zero and 25% across our systematic allocation strategies and funds. The proceeds are invested mainly in high grade government bonds. Where we hold equities, these are all core US S&P 500 positions.

- Across our global fixed income opportunities portfolios, we have sold 80-90% of our high yield bonds and invested the proceeds primarily in high grade government bonds. Due to the risk of inflation and rate hikes, the duration target is closer to 5-years than the 6–7-year duration we would normally apply.

- In our multi-asset strategies, we have also reduced portfolio allocations to Defensive. In some portfolios, we have reduced from 50% equities and 30% high yield to only holding high grade bonds. In other portfolios, the reduction is from 70% or 60% to 10% or 15% equities. Proceeds have been invested primarily in government high grade bonds. Across our Euro denominated mandates, we maintain investments in USD denominated US treasuries.

A world in conflict and the evolving geopolitical reality

Politically and strategically, things are changing fast, and it is uncertain how this will end. What is clear, however, is that China prefers to play its usual “long” game. This means focussing on its own claims for territorial integrity whilst also looking after its long-term strategic alliances, as well as its needs for commodities and energy supplies. We don’t expect China to make itself as dependent on Russian gas as Germany did under Schroeder and Merkel, but we do see a continued strengthening, as over the last decade, of the alliance with Russia. This has now become more urgent for Putin and thereby more useful for China. In the current context, this means that China will focus on the positive aspects of a partnership with Russia, despite the war in Ukraine and Putin’s broader agenda. This was confirmed on Monday, 7th March, when according to Bloomberg, the minister of Foreign Affairs, Wang Yi, used a press briefing to highlight that “…China and Russia will maintain a strategic focus and steadily advance our comprehensive strategic partnership and coordination”. This also comes after the recent Olympics, when Xi hosted Putin and sent him home with a long series of warm wishes for a long-lasting friendship.

From a liberal democratic point of view, there is not much positive in this friendship, but it shows the easiest way forward for Putin. He can partner with China, or he can partner with no-one, so he chooses to partner with Xi and China. While Putin should not be expected to tell the truth, either to his own population or to the West, he is probably not lying to himself any more than he is aware that he is now fighting for something more than his political life. He has not brought to the fight much of the courage or greatness he likes to portray. Thus, he is likely to pursue his military invasion ruthlessly, making the battle painful for Ukraine and for the western world. It is worth remembering in this context that Putin has said that the break-up of the Soviet Union, which killed millions of citizens in both Russia and Ukraine, is regrettable.

In terms of an end to the conflict, it is helpful to see the war in the light of developments in the ex-Soviet Union. Putin has for many years been under pressure because the Russian economy has underperformed. This has led to a forceful repression of opposition across business and political life. In this context, Putin always saw the Maidan revolution and the recent years of Ukrainian growth and freedom as a direct threat to his authority. Recently, events across the Russian border made Putin’s position more difficult. Following the 2020-2021 mass protests in Belarus, unrest in Kazakhstan in early 2022 was crushed with the deployment of Russian led troops. Referring to “Maidan technologies”, Putin thereafter made it clear that he sees this unrest as directed from abroad and declared that he will not allow so-called “colour revolutions” to unfold (Financial Times, 10th January 2022). Russia then increased the deployment of troops along Ukrainian borders, included Belarus in the conflict, and launched an invasion of Ukraine. As horrific as this is, Putin has achieved his first goals of showing his resolve and ruthlessness and thereby preventing the spirit of freedom from spreading further in the former Soviet Union. The immediate problem is that he now needs a way out.

As for the link to China, our assumption is that China will be interested in ending the conflict in Ukraine and is probably willing to take major steps to achieve this goal, if it can act behind the scenes. The problem for China is that Xi hosted Putin as a friend at the Olympics, and who wants to be the friend of an old man who bombs hospitals and civilians? So, Xi and China now need to have a justification for Putin’s actions to save his face. When such a narrative is established (at least internally in China), China will hopefully put political pressure on Putin and Russia behind the scenes to end the conflict. This would be in China’s interest, because it has now established a position as the main future purchaser of Russian raw materials at low prices. It would also reduce the risk for China of Putin’s potential use of nuclear or chemical weapons, which rhymes poorly with China`s broader wish to be respected and recognised as a global leading nation and civilization.

Policy implications in Europe and the US

As highlighted previously, a key question for 2022 is how the markets will deal with inflation and interest rate hikes. The increase in commodity prices will obviously push up inflation and has already led to some speculation that it could force the central banks to hike interest rates. We don’t share this view, because there is nothing much a central bank can do about a supply shock. Rather, we see these price increases more likely leading initially to a lower path of rate hikes. This is already reflected in part in markets, whereby the Fed is now expected to hike 25bps in March rather than the 50bps that was previously priced in. In Europe, the implications will be broader and larger. As the political situation evolves, the EU has started its notoriously slow work on strengthening collaboration across countries. As of now, it looks like this will end up including more issuance of collective emergency debt and the disbursement of financial support for those countries hosting more refugees and those needing help with a transition to non-Russian green energy. As for the ECB, the initial answer was to push forward the end to QE. There is, however nothing new in the ECB making smaller and larger policy mistakes before getting things right, so we would not push forward rate hike expectations just yet.

In terms of fiscal policy and the green transition, the direction also looks reasonably certain, with governments across the European continent declaring their will to spend more on defence and promising a fast transition away from reliance on Russian gas and oil. It looks as though the easiest

thing for everyone to agree on will be the need for an accelerated green transition and thereby for renewed fiscal spending, which should lead to stronger future growth down the line if and when peace prevails. When it comes to the spending on such future energy independence and a green transition, the question will be what can now be called green and what can be called ESG.

Figure 2: US Manufacturing ISM (business confidence) signals continued growth

For example, is it good (G) Governance for a utility company, which claims to be an ESG champion, not to have governance in place which ensures the cancellation of a contract with a supplier owned by a government invading other countries in central Europe? Is it socially responsible when the company’s CEO says that if it doesn’t trade Russian gas, others will? The same argument could be used by any enterprise facing a steady demand, whether legal or illegal. Rather than a confrontation on such double standards, we expect that the debate will reach a consensus: the important thing will be to act as well as possible in future; investment in companies will be ESG compliant even though their management did not prevent them from being dependent on Putin’s Russia for their growth. Independently of the fact that many from the left wing all the way to Putin himself and Trump, have warned them about the risk that Putin would one day try to re-establish respect for Russia with military force.

In currency markets, events such as these are normally associated with a strengthening of the US dollar, and we think this is also likely to be the case this time. The reason is that if peace returns to Europe, or even if the conflict turns into deadlock, the Fed is still likely to hike this year and most likely to reach a level of 2-3 percent the next few years.

Market risks and positioning:

Until recently we have remained fully invested in equities and high yield since the first half of November 2020. Our algorithms now show clear signs of a deteriorating risk-return trade-off in the progress of the recovery, and we have therefore reduced portfolio risk and moved from our “Positive” portfolio allocations to “Defensive”. For the time being, our view of the risk climate can be summarised as follows:

- The Federal Reserve kept supporting growth through 2021 and thereby turned its policy from counter-cyclical in 2020 to pro-cyclical in 2021. As it lost control of inflation, an incremental tightening was introduced, with both rate increases and a reduction in QE, with a decelerating recovery. Apparent insecurity and lack of agreement across the FOMC increases the risk of policy mistakes in these difficult times. So does the latest energy price shock.

- Large scale changes to the business environment and a collapse in the property sector in China have led to a sharp economic slowdown in 2021 and substantial losses across credit and equity markets. This was initially a Chinese tech issue, but it has increasingly become a global tech phenomenon, eating into investor sentiment. Now China needs to re-accelerate growth, but they also need to keep control of public opinion: a difficult balancing act.

- Interest rate increases and credit spreads widening, together with a cyclical deceleration, have hurt performance across equity markets in Asia and Europe and, in 2022, also in the US. There is a risk of a change in sentiment from a bull market mentality to a more nuanced view of buying on dips.

- The German Chancellor Scholtz has said that he will not stop importing Russian oil and gas. As the horrors of the war continue, there is a chance that the German public will disagree with Scholtz’s view and demand more action against Putin. We could therefore see an accelerated energy crises and a new energy and market shock.

Key drivers of this recovery have been easy monetary policy and the extremely strong corporate profit recovery, driven by low financing costs and strong final demand on the back of supportive politics. Corporate profits have therefore been supporting markets, but momentum is declining.

In summary, our algorithms do not signal markets will necessarily collapse, but the risk of a prolonged correction is increasing, meaning that the risk-return trade-off is deteriorating, and we have adjusted our positioning accordingly. The situation is different from March 2020, when we last moved to Defensive. Back then, both the market signal and the macro part of our signal deteriorated sharply. This time around, the macro signal remains in positive territory, and we don’t expect the US economy to fall into a recession. The latest fiscal bill in the US is helpful in this respect. A consistent financing plan for new EU funding would be good as well. Clarity on policy and priorities from the ECB and the Fed would also help. In any case, the consequence of the current state of financial conditions is that a return to a higher allocation of equities and high yield bonds could happen faster.